It’s time to talk about another board game here on A Reception Collection. This game, Akrotiri, is a focal point in my thesis research. I recently finished writing a chapter that addresses it in detail, and it’s making appearances elsewhere in my writing. The way Akrotiri engages with ancient history is absolutely fascinating: let me tell you why!

Plenty of board games, ancient Mediterranean-themed or otherwise, involve two distinct groups of people. There are the players, who exist in our physical world as well as the imaginary world of the game. Then, there are people who only exist within the game, in an imaginary play-setting. If you enjoy video games or tabletop role-play, think of these people as NPCs (non-player characters). They exist to interact with the players and further the in-game narrative, but don’t have much characterization beyond this. These people could be members of a different culture from the players, like the Gauls, Picts, and other Celtic peoples in Roman games like Hadrian’s Wall. They might even be members of an entirely different species: sci-fi titles such as Starfarers of Catan and Ad Astra often feature aliens that players can encounter. Akrotiri’s players interact with a different group of people, but these two groups are not differentiated by place of origin, ethnicity, or species. They’re separated by time.

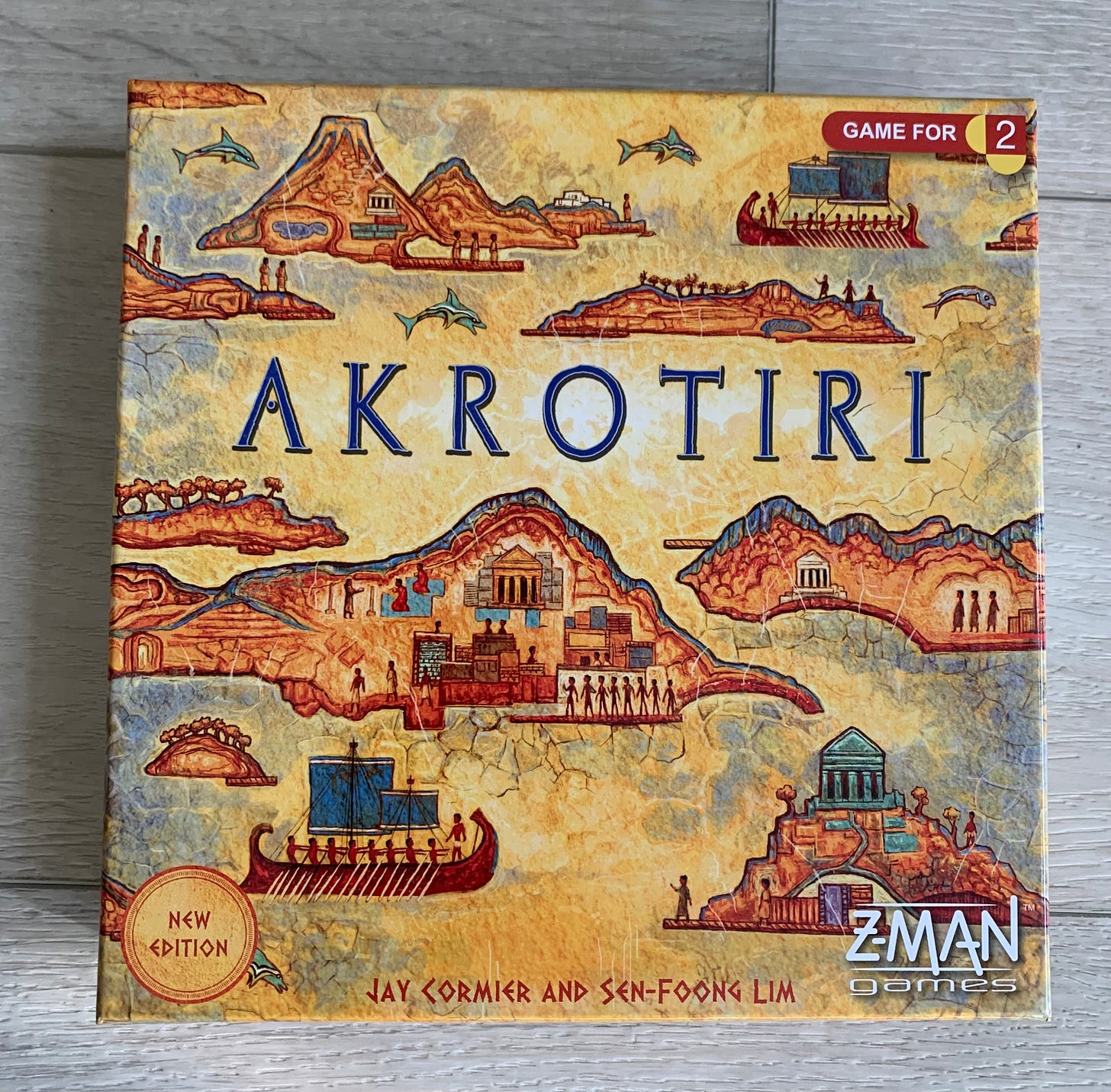

Both the player characters and the in-game people of Akrotiri are Greeks, living and working in the Cycladic archipelago in the Aegean Sea. The players take on the role of Greek merchants in the classical period, around 500-400 BCE. They navigate sea routes through the Cycladic islands, gathering resources and trading them for money. In keeping with modern Cycladic aesthetics, one player’s pieces are white and the other’s are blue.

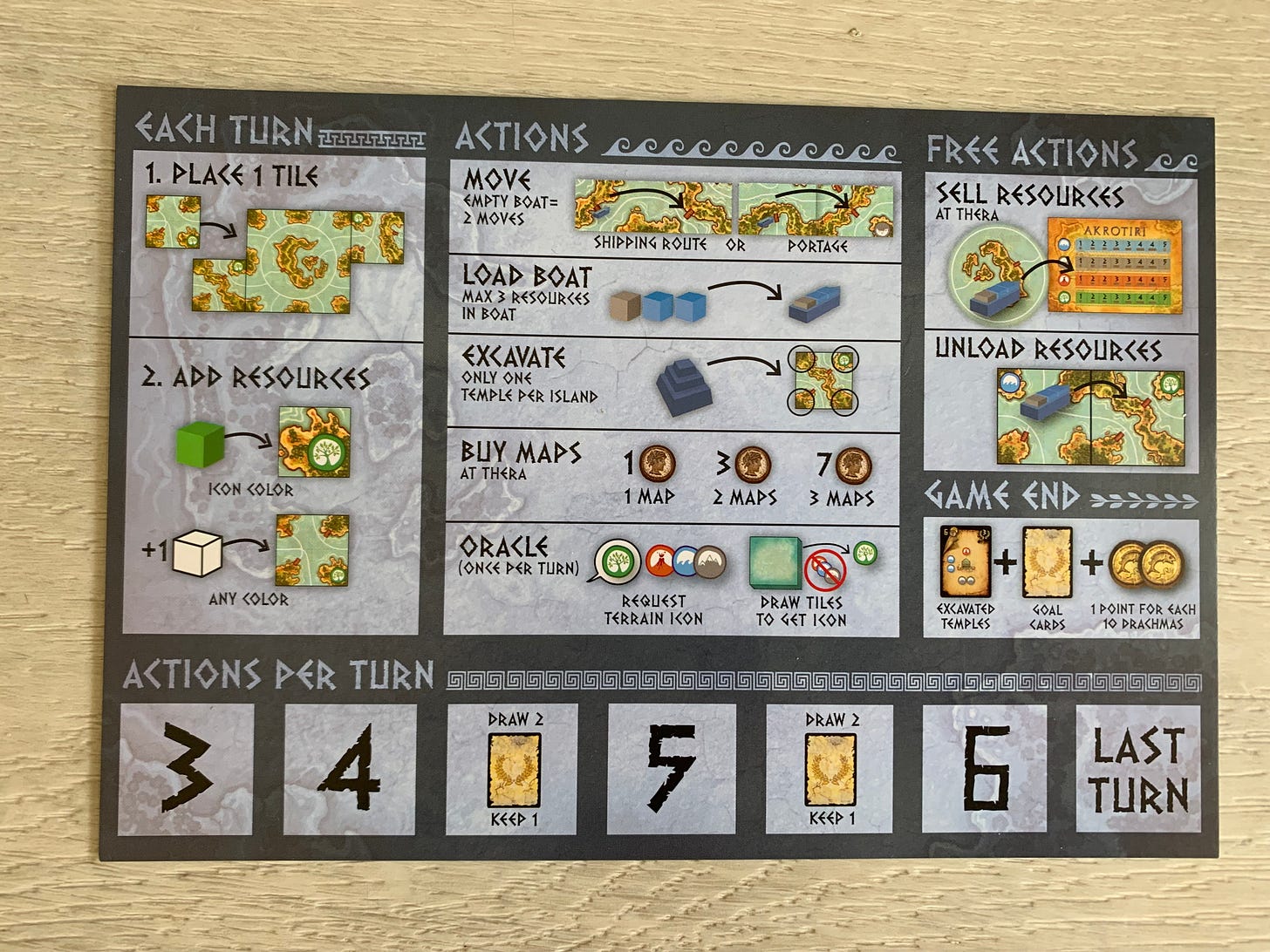

Akrotiri’s board is modular. This means that it’s not a solid, single object, but rather a formation of tiles. The game begins around a large central tile, which represents the Greek island of Thera, then expands from there. The players lay new tiles connected to the Thera piece as the game unfolds, gradually creating a map. This mapmaking process simulates charting untrodden territory, with players slowly discovering new islands and sea routes. For classical-period Greece, when the entire Aegean sea was well-charted and thoroughly explored, this is a little anachronistic. However, I can forgive the designers of Akrotiri, because a modular board gives players a sense of real excitement at uncovering new territory. This design also makes the game interesting to play over and over again, since the map is slightly different every time. From a design perspective, it’s smart to give players an incentive to return to your game.

The uncharted land in Akrotiri offers up more than just new resources: as they explore the islands, the players come across Minoan ruins. They can spend resources to excavate these ruins, earning ‘fame points’ in the process: these ‘fame points’ are a key component of winning the game. The game implies that these Minoan discoveries will grant the player’s in-game personas some form of recognition and perhaps even glory. Thus, the world of Akrotiri is one where people are interested in their own past, and curious about the remains of societies lost to time. They are tangibly rewarded for this curiosity through the point system. The game’s rulebook emphasizes this focus on discovery: its introduction encourages players to find the Minoan ruins “before time forgets them, and History forgets you.” Note the capitalization of the word ‘History.’

Although the concept of an archaeological expedition is another anachronism in an ancient Greek setting, we know that at least some people in the ancient Mediterranean were interested in the distant past, and made efforts to learn more about it. This is a perfect place to introduce you to one of my favorite historical figures: let’s talk about Pausanias.

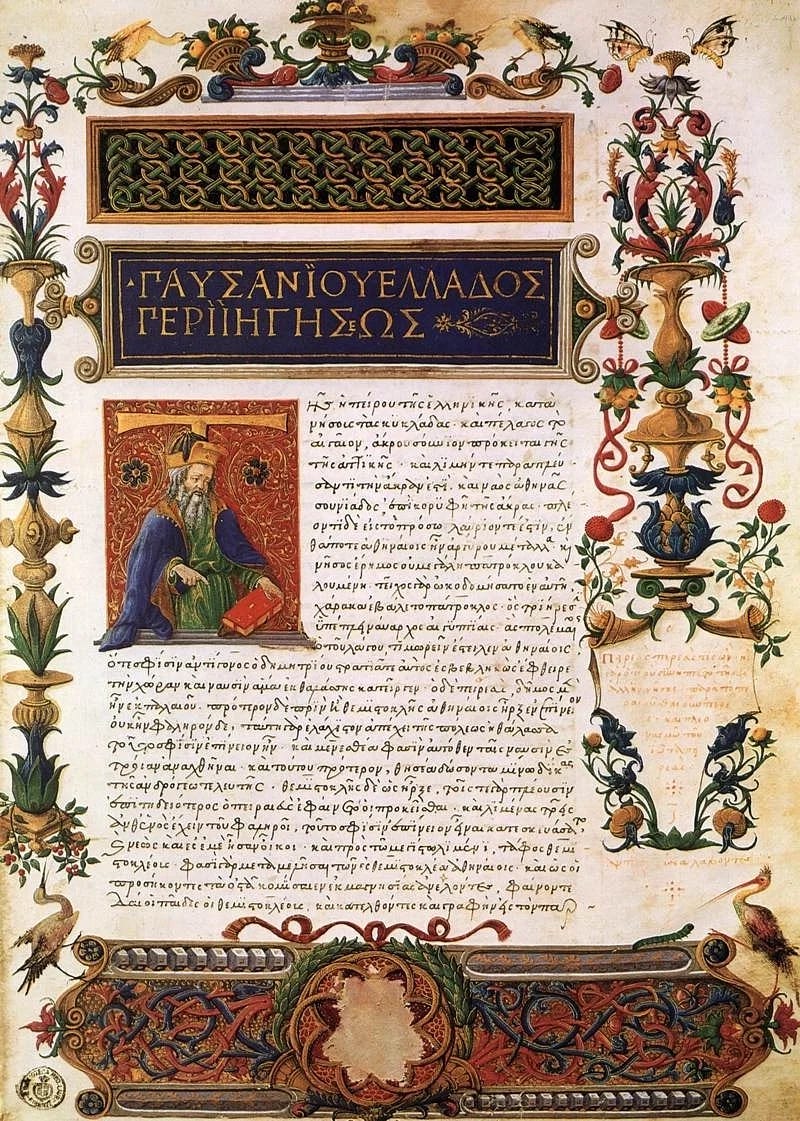

Pausanias was a writer and traveler in the Roman empire in the 2nd century CE. His family were of Greek descent, and he maintained a lifelong fascination with his ancestral history and culture. The classical and archaic periods weren’t as temporally removed from him as they are from you and I, but I still feel a kinship across the centuries with Pausanias because of our mutual love of ancient Greece.

Throughout his life, Pausanias travelled across the Eastern Mediterranean and took extensive writing notes. He eventually compiled these notes into his masterpiece, the Guide to Greece. I could ramble on about Guide to Greece and how entertaining it is to read, but let’s stay within the realm of Akrotiri. (Given that it’s from the Roman imperial period, but discusses pre-Roman Greece, does Pausanias’ writing count as ancient Mediterranean reception? I’ll have to ponder that.)

Guide to Greece makes ample allusions to the Minoans. Pausanias treats them as a point of curiosity, encouraging his readers to visit sites that feature their architectural remains. The sections of Guide to Greece that deal with Crete, the Minoan’s locus of power, take on a veil of mythicality and a sense of the distant past. Myths and an interest in distant history show up elsewhere in Guide to Greece, but I argue that these themes are at their most heightened when Pausanias discusses Crete and other Minoan places. In other parts of his text, he talks more about contemporary architecture. In Athens, he brings up the emperor Hadrian’s interest in the city. Hadrian was emperor for the first decades of Pausanias’ life, and many of the building projects he sponsored in Athens still stand today.

I’m getting sidetracked: back to the Minoans! Nearly every time Pausanias addresses Crete in Guide to Greece, he depicts the island as a distant place both in terms of location and of time. It’s far from mainland Greece, full of ancient myths, and soaked in history. Pausanias’ perception of the distant Greek past may have been written several centuries after the classical period in which Akrotiri takes place, but the game neatly mirrors his outlook on the Minoans.

Primary source texts such as Guide to Greece reveal that looking back at the past is nothing new. However, placing one’s audience in the role of ancients looking to a past that is distant even by their standards, as Akrotiri does, is something of a novel concept. All the other games I’ve encountered in my thesis research take place in antiquity, and only concern the present moment in-game. There are also some games themed around archaeology that encourage their players to look back at the past within their imaginary settings: however, these games generally take place in the 19th century or later. The study of archaeology may only be a few centuries old, but we humans have always been interested in our own past.

Akrotiri beautifully displays this retroactive fascination, and invites its players to think of it as a human constant. It reminds us that “antiquity” is a very long-ranging category of time. The game highlights how the construction of history is nothing new, and that people have always been interested in their own past. It depicts interactions between two periods of ancient Greek history, while giving us a chance to interact with antiquity in a creative new way. Of course, Akrotiri’s players get to do all this complex historical musing while acting sneaky and outfoxing each other’s attempts to earn fame points! It’s this unique juxtaposition that keeps drawing me back to this game, and compelling me to share it with others, both here and in my thesis research.

This board game analysis is modified from a draft section of my thesis. For the sake of academic honesty and further reading, here are my sources:

Cormier, Jay, and Lim, Sen-Foong. Akrotiri rulebook. Asmodee, 2014.

Habicht, Christian. "An Ancient Baedeker and His Critics: Pausanias' ‘Guide to Greece.’" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129, no. 2 (1985): 220-224.

Lambert, Peter, and Weiler, Bjorn (editors). How the Past Was Used: Historical Cultures, c. 750-2000. Oxford: Published for The British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2017.

Levi, Peter, translator. Guide to Greece Volume 1: Central Greece. By Pausanias. Revised Edition. Penguin Books, 1979.

Levi, Peter, translator. Guide to Greece Volume 2: Southern Greece. By Pausanias. Revised Edition. Penguin Books, 1979.

Pretzler, Maria. “Turning Travel into Text: Pausanias at Work." Greece & Rome 51, no. 2 (2004): 199-216.