I’d like to introduce you to one of my favorite board games of all time. My personal gold standard for historical gaming. This is Klaus-Jürgen Wrede’s 2004 masterpiece, The Downfall of Pompeii.

I love tabletop gaming almost as much as I love ancient Rome, so it’s a bit of a no-brainer that this title resonates with me so strongly. But my fondness for Downfall of Pompeii goes beyond its theme, into how it engages with one of the most iconic events in Roman history. This game sparks the imaginations of its players and gets you thinking about Pompeii in varied, exciting ways. Also you get to toss things in a model volcano; what’s not to love?

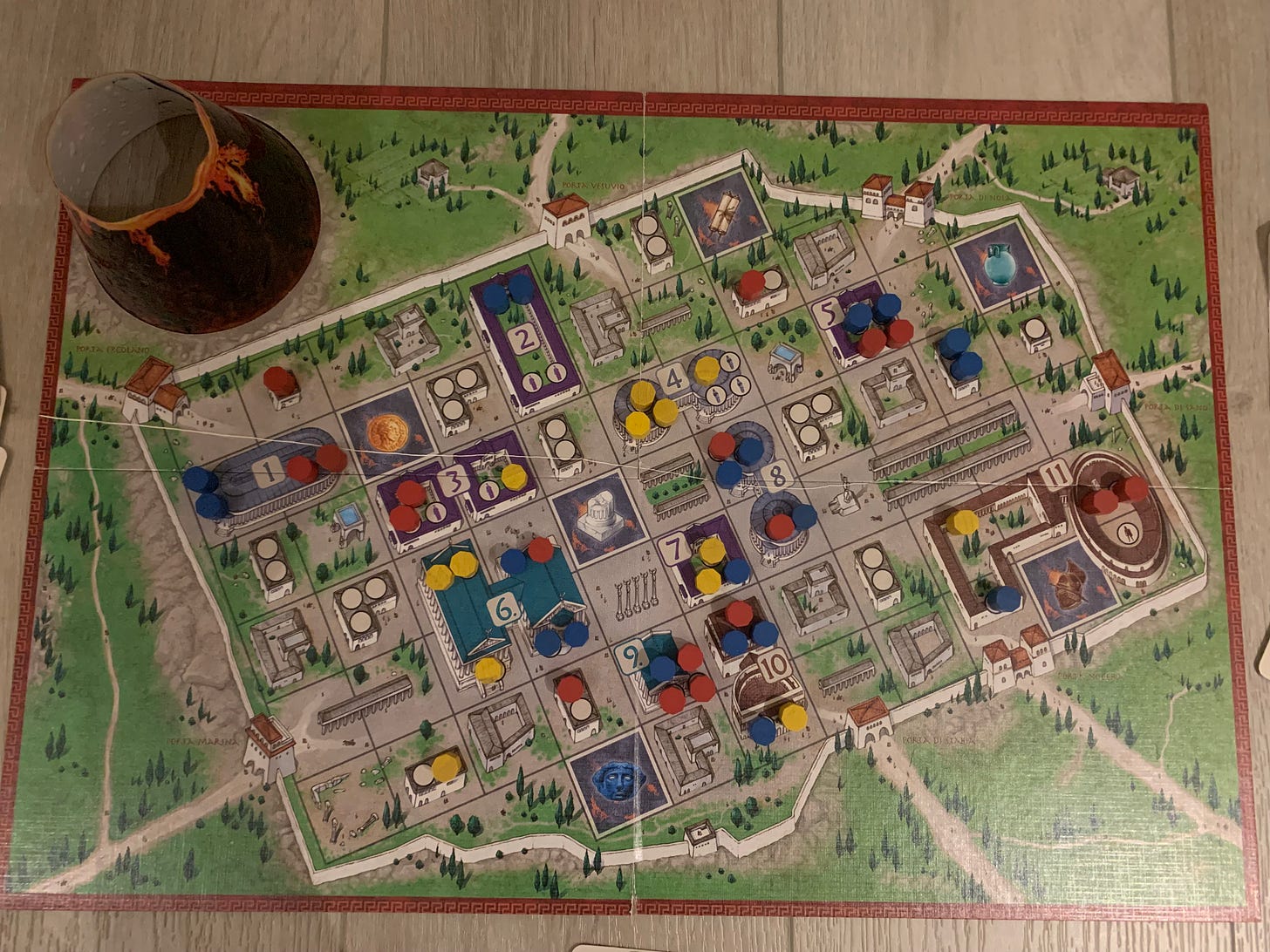

Downfall of Pompeii is played in two phases. First, players take turns placing pieces, which represent inhabitants of Pompeii, in different building on the board. Roughly halfway through the game, Vesuvius erupts. Players then shift from placing their pieces to moving pieces around the board, trying to get them through the city gates and away to safety. At the same time, they also cover the board in tiles that represent lava.

If you cover an opponent’s pieces in a lava tile, you get to drop said pieces into a little model Vesuvius; this makes your opponents lose points, and you get the (immense!) satisfaction of dropping stuff in a volcano. At the end of the game, the player with the most survivors wins.

I bring up these two phases because they don’t just exist for the sake of gameplay: they represent two real phases in Pompeii’s history. In 62 CE, Pompeii weathered an intense earthquake that levelled many of its buildings. The first phase of Downfall of Pompeii takes place between the aftermath of the earthquake and the eruption, with people rebuilding and new inhabitants moving in.

While the first phase of gameplay represents about a decade and a half of Pompeii’s history, the second phase, when Vesuvius erupts, takes place over only a day. This time-lapse video gives you an idea of how long the volcano took to destroy everything:

Many historical board games that focus on civilian life take place over indeterminate periods of time, and don’t seek to replicate specific events. This makes Downfall of Pompeii’s approach a fairly unique one. It’s rare to see a game that doesn’t have a military theme, deals with a specific historical event, takes place over a set period of time, and incorporates different phases of play. I wonder if Klaus Jürgen-Wrede was at all inspired by military games during his design process.

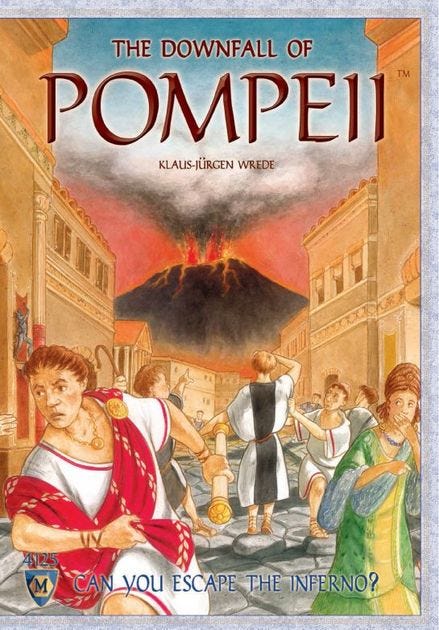

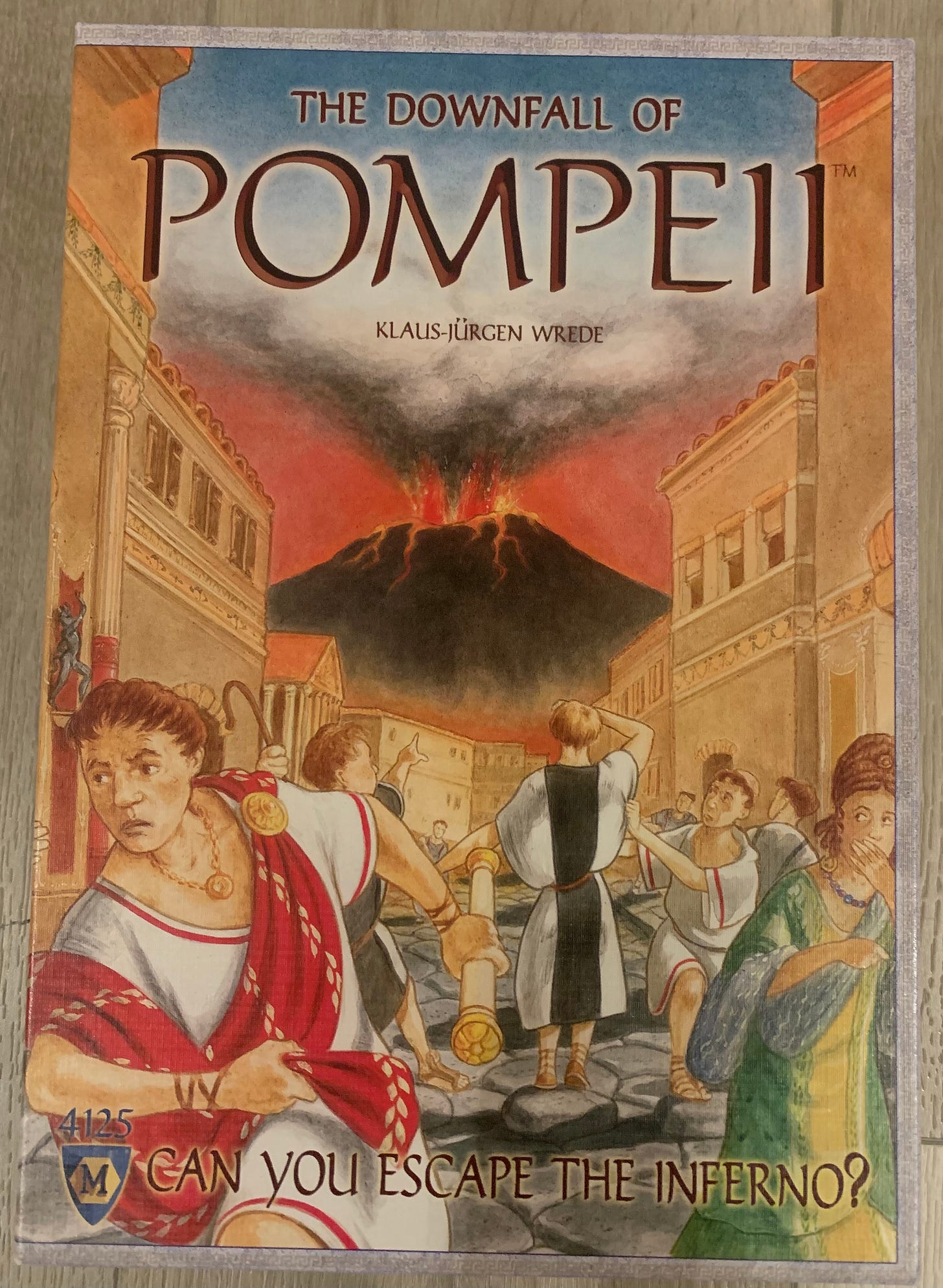

The artwork in Downfall of Pompeii isn’t quite as unique as its historical approach; there are plenty of other board games that look like it. However, its attention to detail and close ties to the archaeological record make it stand out. Let me take you on a little journey through the components of this game.

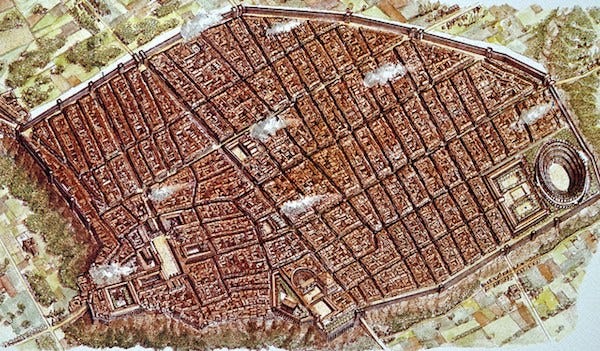

There’s something inherently cozy and nostalgic to me about Downfall of Pompeii’s box cover, even though it depicts people fleeing from a volcanic eruption. Maybe it’s because the soft, pencil-drawing artwork is in the same style as the turn-of-the-millennium educational library books I used to pour over as a kid. The game artwork inside the box is in a similar style. The board depicts a gridded version of Pompeii that’s remarkably close to the city’s actual layout. For comparison’s sake, here’s a digital map of how the city would have looked in 79 CE, alongside Downfall of Pompeii’s version.

Obviously, the board game can’t depict every single building in Pompeii, and it plays around with the locations of a few noteworthy places such as the Forum, some of the city gates, and the theatre, but overall, I’m impressed by how close it comes to Pompeii’s real urban layout. By nature, board games always have to simplify and abstract the places they illustrate, sacrificing detail for the sake of a playable game.

This simplification is also apparent in the citizens of Downfall of Pompeii. These people appear on cards that players use to dictate where they put their pieces on the board.

Four Roman people appear in the game: a priestess, a wealthy woman with fancy clothes and jewelry, a toga-clad political man (complete with dramatic hand gestures!), and a gladiator. I would have loved to see a bit more working-class representation here; a shopkeeper or some kind of manufacturer like a smith or a weaver would have been nice. That being said, I understand why the game design team chose these specific people to represent Pompeii’s population as a whole; they all personify important cornerstones in our modern perception of Rome. Note the even gender split here; the priestess and noblewoman could have easily been represented by men, but they’re not, and I’m pleased.

There’s artwork of various material objects scattered around the board, such as a coin, a glass container, and a gladiator’s helmet. These material objects also make another appearance on tiles that come into play in the second phase of the game, when Pompeii gets covered in lava and citizens need to flee the city. I’m not sure if these illustrations are based on any specific artifacts from Pompeii’s archaeological record, but they’re definitely taking ample cure from Roman material culture. The scroll is a particularly nice touch here: the eruption of Vesuvius preserved thousands of scrolls exactly like this one. There’s some very exciting archaeology going on right now, using specialized x-rays and machine learning to read these now-carbonized scrolls without unrolling and destroying them. I, for one, can’t wait to see if there’s any lost Greek or Roman literature written in them!

Between the buildings on the board, the tiles with small objects, and the cards with people, Downfall of Pompeii gives us a pretty decent survey of what we know about this famous ruined city. Even though the game takes place in ancient Rome, it reminds its players of subsequent history, especially of later archaeology. When pieces get “killed off” and dropped into the model Vesuvius, we’re reminded of the preserved bodies left in the real Vesuvius’ wake. The game constantly reminds its players of death and destruction: at the same time, it does a wonderful job reminding you that Pompeii was filled with people, and that their lives were as vivid and interesting as our own.

When I play this game, my fellow players and I often find ourselves complaining about our neighbors, forming our pieces into little “family groups,” and speaking as if we were actual gladiators, or senators, or regular people. This miniature Roman role-playing isn’t part of the game’s rules, but Downfall of Pompeii’s artwork and gameplay encourages our imaginations, inviting us to form connections between our lives and those of ancient Romans. Its this focus on everyday people and their lives, paired with evocative artwork, that makes Downfall of Pompeii more than just a historical simulator. This game is an interactive piece of historical reception that reminds us of death, but also that people have always been people, around the world and across time.

All uncredited photos were taken by me, December 2023.

"Don't mind me, just making a spot of room for Great Uncle Marcus …"!

fascinating... learning about pompeii wrecked me in school, i can only imagine what i'd've done if my mom had brought home this game