You can learn a lot about a given point in history by looking at its children’s media. This media is, of course, designed to entertain kids, but it’s also meant to help them navigate the world. Even media that’s not overtly educational subtly reinforces ideas, ideologies, and beliefs that the adults who created it think children should absorb. Today on A Reception Collection, I’ll take you through a particularly interesting example. Let’s explore a book that encourages kids to think critically about gender and agency, while retelling some timeless stories.

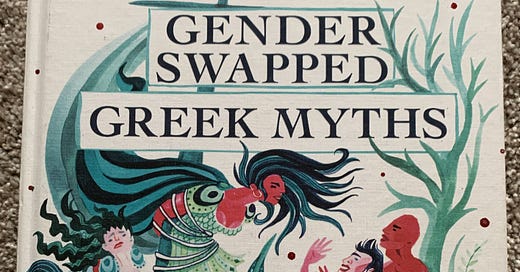

This is Gender Swapped Greek Myths, a 2023 book compiled by husband-and-wife team Karrie Fransman and Jonathan Plackett. Plackett is a digital creator who’s worked on a wide variety of projects, and Fransman is a comics illustrator. They’ve worked together on several artistic endeavors, including this book’s companion, Gender Swapped Fairy Tales. Both books operate under a simple, yet intriguing premise: what if the men in classic stories were women, and vice versa? Fransman and Plackett don’t alter the plots of these tales, only the genders and names of the characters and some of the language when necessary (fathers become mothers, maidens become bachelors, you get the idea).

Looking at a recently published mythology book for kids has been an interesting experience for me. I’m not sure what I would’ve thought of Gender Swapped Greek Myths when I was small (I was very particular about my mythology books, especially if they took creative liberties!), but reading it with adult eyes was delightful.

The matriarchal world of Gender Swapped Greek Myths was a joy to discover. I found myself looking forward to hearing what new characters would be called: feminized hero names like Thesea and Odyssea roll off the tongue so well! Beyond simple changes in nomenclature, the themes of Greek mythology take to a gender switch remarkably well. Since all the monster-killing, beauty-rescuing heroes here are actually heroines, the book is packed with descriptions of women’s physical strength and bravado. These muscle-filled descriptions border on sapphic territory, but also serve as an exciting female power fantasy. If, like me, you harbor lifelong dreams of being a warrior princess, this is stirring stuff!

The stories of these heroines serve as pretty classic inspirational material, like their male counterparts in more standard myth retellings. With the heroines as a launchpad for the imagination, young readers can pretend to have magical powers, or superhuman strength, or a cleverness that rivals the gods. Like their mythological equivalents, these characters are also quite flawed. They make crucial mistakes, go through bouts of senseless violence, and engage in all the other trappings of ancient Greek heroism. I find this fascinating: it feels like a lot of “strong female characters” in modern media aren’t this flawed, almost as if their creators are afraid to make them complicated people. They’re often stoic, overly competent foils for male characters, who are allowed to grow and change, get things wrong, and overall act more relatable and human. Obviously not all modern media falls into this trap, and there are some wonderful imperfect-yet-powerful female characters out there. However, the brash warrior heroines of Gender Swapped Greek Myths feel like a fresh change of pace in today’s media landscape.

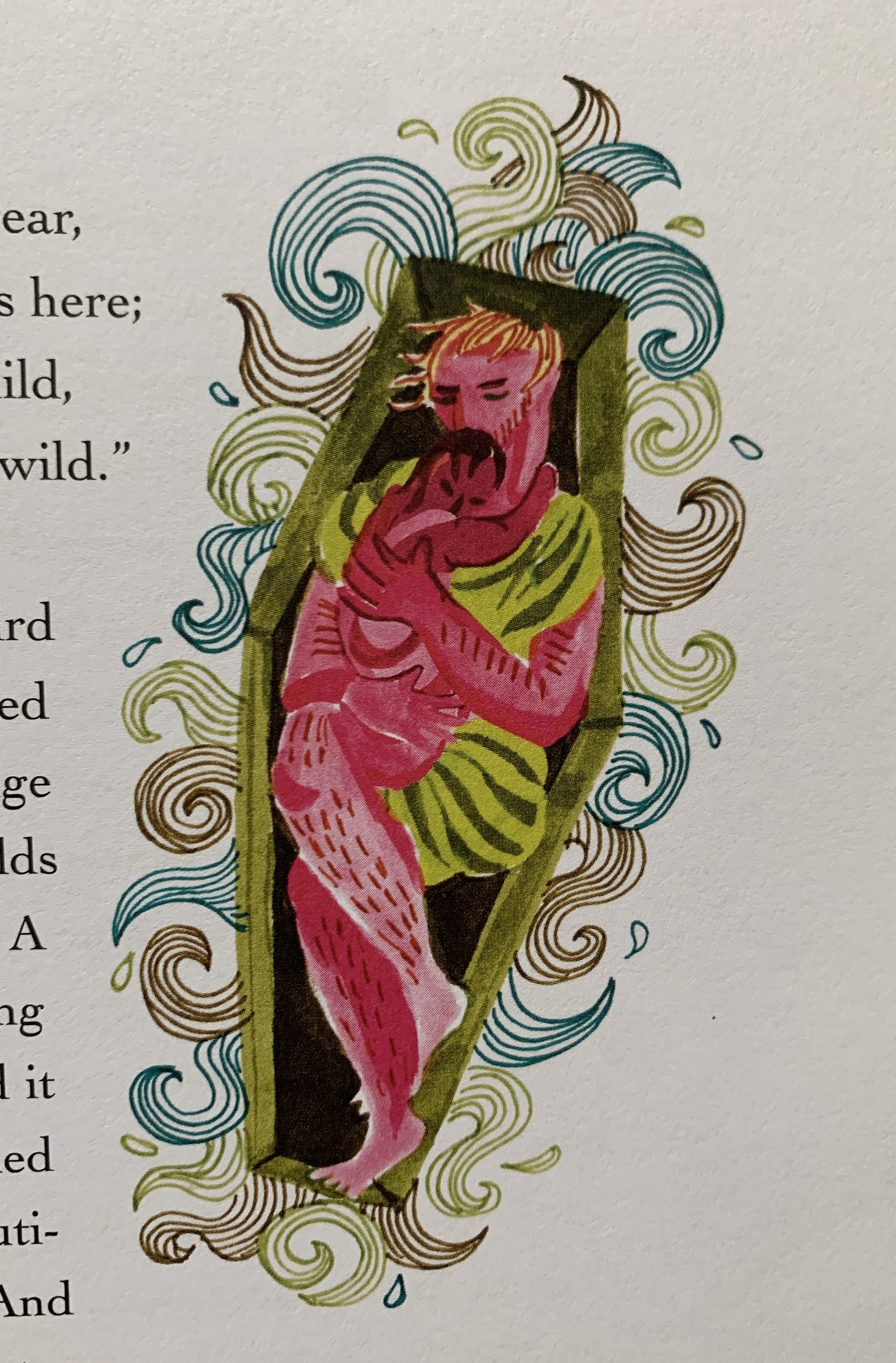

The matriarchal dreamscape of Gender Swapped Greek Myths goes beyond just warriors. The switch from kings to queens and gods to goddesses creates a wealth of powerful older women in positions of authority and respect. Since the nymphs and princesses of Greek mythology also go through a gender switch, this story-world is full of delicate, sensitive young men, including quite a few male damsels who get captured and need rescuing. Prince Andromedus is perhaps the most overt, chained to a cliffside until the heroine Persea swoops in to save his life and win his heart. I find these characters just as much of a feminist fantasy as the warrior women: I spent plenty of my childhood pretending to be a heroine, and a lot of my imaginary heroism involved rescuing pretty boys in distress. These characters also give boys a chance to explore their vulnerable, sensitive side, which feels more important than ever in our toxically masculine times.

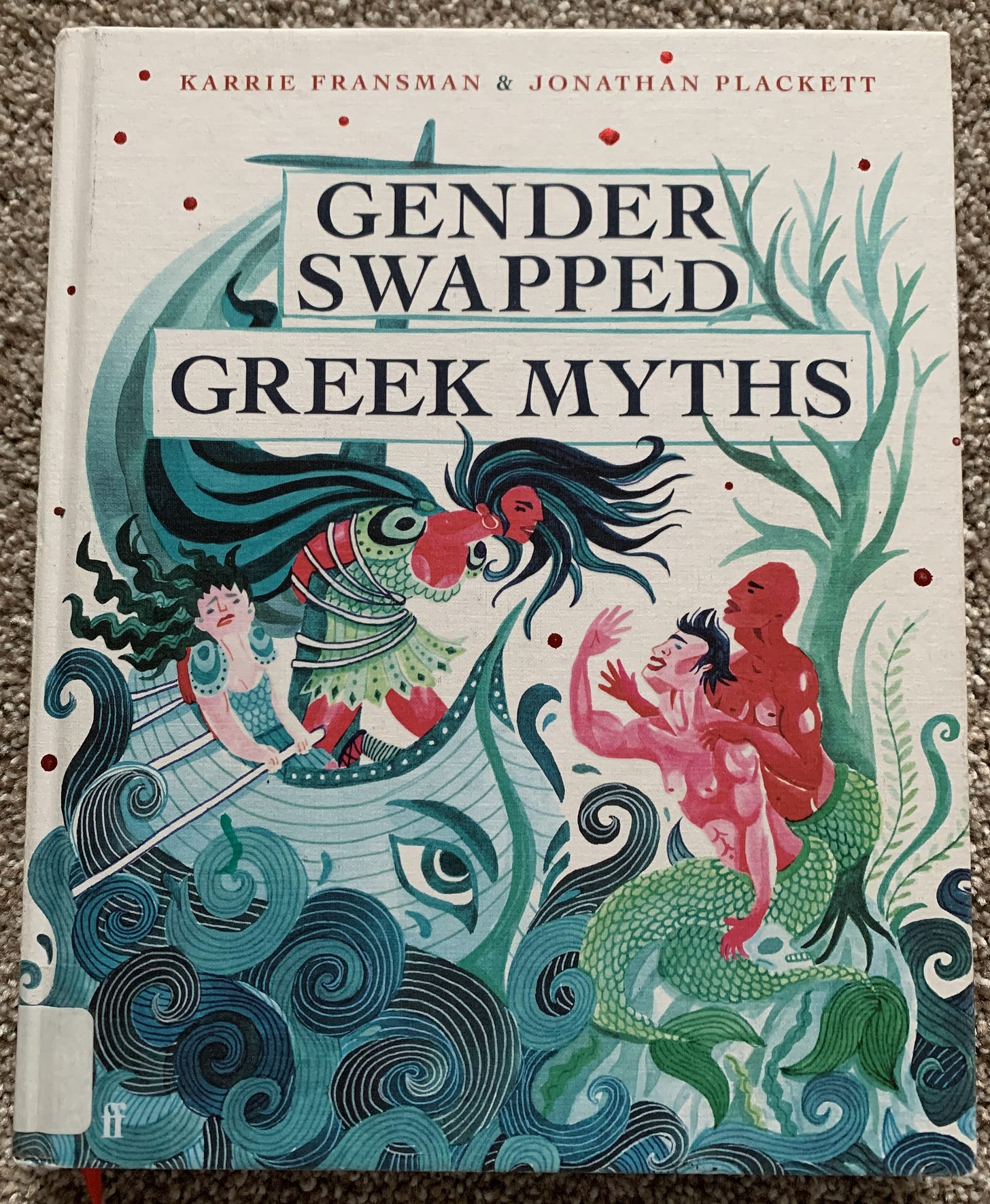

Gender Swapped Greek Myths offers up a more varied catalogue of male characters than just boy-damsels. Greek mythology has no shortage of positive depictions of motherhood: Danae and Demeter are a pair of my favorites. With a gender swap at play, they become devoted, often very tender fathers. I appreciate seeing these sweet, affectionate portrayals of fatherhood, especially in a children’s book. These mythological dads spend lots of time with their kids (sometimes they’re the sole caregivers for their kids), and they can be fiercely protective of their offspring. I hope this book’s young readers see their own dads reflected in these characters.

It’s worth mentioning that Fransman and Plackett didn’t craft their myth reworking from scratch. The text of Gender Swapped Greek Myths began with public-domain books of mythology for children from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Fransman and Plackett created an algorithm to swap gendered words, then manually doctored the altered text until they liked the results. Thus, Gender Swapped Greek Myths is a text not only in conversation with antiquity, but with children’s literature from a more recent point in time.

Funnily enough, I went into this book without knowing that it was cut from long 19th century cloth. I listened to it in audiobook form before borrowing a physical copy from the library. The audiobook, which is delightfully read by Fransman and Plackett, saves the explanatory authors’ notes for the end, and starts with a dive straight into the mythology. However, I figured out that the stories are altered because one of them, the story of Persea and Medus, is reworked from an old fairy tale book I read as a kid! Andrew Lang’s Blue Fairy Book, originally published in 1889, mostly contains classic western European fairy tales, but also features a couple of heavily watered-down Greek myths. One of these is ‘The Terrible Head,’ a version of the Perseus myth that irritated my child self to no end. I hated how Lang scrubs the Greekness out of the story: he eliminates a lot of Perseus’ interactions with the gods, leaves out place names that situate the story in ancient Greece, and generally abandons what makes the Perseus story special.

There is, however, one redeeming quality in ‘The Terrible Head.’ Near the beginning of the story, Danae and her baby Perseus are set adrift at sea, because Perseus is destined to kill his grandfather and because women in Greek mythology can’t catch a break. Andrew Lang (or possibly Nora Lang, his uncredited wife who penned large swaths of the Fairy Books) wrote Danae a genuinely sweet, slightly haunting little lullaby to comfort her baby. Even as a kid with snarky opinions about mythology, that lullaby struck a chord with me. Fransman and Plackett make a lot of much-needed alterations to Lang’s text, including the obligatory gender swap, reinserting the distinctly Greek setting, and bringing back the gods, but they kept the lullaby. In one of Gender Swapped Greek Myths’ most tender portrayals of fatherhood, prince Danaus sings it to his baby daughter Persea. When I read this, memories of ‘The Terrible Head,’ a text I’d forgotten existed, came flooding back to me!

I have mixed feelings about Fransman and Plackett’s choice to disrupt Victorian and Edwardian text, as opposed to writing something from scratch. Their source material gives Gender Swapped Greek Myths an old-fashioned quality: sometimes this lends the stories a timeless mythicality, but in other places they read as rather dated. This is particularly true of the dialogue, which can flow in a stiff and overly formal fashion, with ample ‘thees’ and ‘thous.’ The update on long 19th century text is a worthwhile thought experiment: I’ve already highlighted the ways in which it subverts some pervasive gender norms and creates some fantastic new characters. It would be subversive enough to flip the genders in text from antiquity, but the experiment gains more resonance because it’s performed on text from such a repressive, violently heteronormative point in history. However, as a readable children’s retelling, the end result is imperfect. I almost wish the authors had updated the language beyond the gender swapping, or perhaps written their altered myths from scratch.

The use of text from the Victorian and Edwardian periods influences the language in Gender Swapped Greek Myths, but also affects the selection of stories in this retelling. There are plenty of Greek myths that were altered to be palatable for children in the long 19th century, as well as other stories that never made the cut of myth retellings from that time period. Some of these are stories that aren’t included in Gender Swapped Greek Myths, but I really wish had been incorporated: imagine an Iliad starring a lesbian Patroclus and Achilles!

Other stories are fantastic in their original form, but lose some magic with the gender swapping treatment. In this light, I understand why Fransman and Plackett left them out of their book. These include the many Greek myths where a vengeful woman ruins her husband’s life, usually for completely justifiable reasons. Gender-Swapped Greek Myths features a few lines about the warrior queen Agamemnia and her murderous husband Clytemnestrus, but doesn’t tell their story outright. Jason and Medea are left out altogether: I understand why, even though their story is one of the finest in Greek mythology. The original story of Medea is a perennial tale of female resilience, rage, and revenge. With the genders reversed, it devolves into a horror show. In our still-patriarchal society, there’s nothing empowering or exciting about a man murdering his daughters, poisoning his romantic rival, and leaving his grief-stricken wife to suffer alone. There technically shouldn’t be anything exciting about a woman doing all that, but millennia of gender-based oppression give Medea some serious allure. She’s a female power/revenge fantasy on par with the heroines in Gender Swapped Greek Myths, and she’s not the only mythological woman to assume this role.

If the authors had left out stories like those of Clytemnestra and Medea purely because of modern attitudes towards gendered violence, I imagine they wouldn’t have touched the myriad of Greek myths that focus on women getting assaulted. The Victorians apparently didn’t think these stories were inappropriate for children, smoothing out the sexual and violent parts with carefully chosen language. Thus, Gender Swapped Greek Myths features stories like those of Io and Persephone: the book’s world is full of lustful goddesses, having their way with vulnerable young men. I’m not opposed to this inclusion on principle: these stories appear in plenty of more modern retellings for children, with the original genders in place. The swapped versions draw attention to the imperfections of a society with a gender hierarchy, regardless of which gender holds power. Fransman and Plackett are always careful to point out in interviews, like this one with the Guardian, that their matriarchal myth-world isn’t a utopia, it’s just a little bit different from our own. Gender disparity exists here in full force, albeit in a way we find unfamiliar.

While Gender-Swapped Greek Myths is a worthwhile thought experiment, and I appreciate the sentiment behind it, I think the project misses out on some of the enduring resonance of ancient mythology. Greek myths have always made my heart sing: I loved them as a small girl first moving through the world, I loved them as a patriarchy-weary undergrad, I love them now. I love them despite all the violence and misogyny that lurks at their core. They present a world where men can do what they want and get away with it: I live in a time and place where that rings all too true.

Despite their subaltern status in ancient Greece, their mythos is brimming with women. These women defy patriarchal oppression. They cleverly find agency within normative social structures. Perhaps most poignantly and relatably, they do their best to get through the day and live a decent life. We don’t need to rework their stories to celebrate and honor them. A gender switched version of these myths creates fantastic new characters, male and female alike, but it also occludes the wonderful women who populate myths from antiquity. A matriarchal dreamscape is great fun to daydream about, but it doesn’t have the same evocativeness and punch as the actual world of Greek mythology, where women are cunning and powerful and fierce, despite the odds so terribly stacked against them.

I don’t want to come across as too critical of Gender Swapped Greek Myths. Fransman and Plackett’s hearts are in the right place, and their work is tremendously entertaining, not to mention visually lovely. The book is deliberately thought-provoking: if anything, the rambling I’ve come up with here is proof of the authors’ concept. I appreciate how Fransman and Plackett encourage readers of all ages to think critically about mythology and its interplay with gender and power: they acknowledge that kids are smarter and more analytically capable than adults often give them credit. It’s heartening to see that intelligence and curiosity fostered in this modern mythological offering. You’re never too young to start criticizing the patriarchy, never too young to think imaginatively about old myths, and never too old to enjoy a good illustrated storybook.