Who doesn’t love a good dungeon adventure? They’ve been a mainstay in tabletop gaming for decades, and for good reason. Dungeon-themed games have provided generations of players with exciting monster encounters, thrilling traps and puzzles, and premium opportunities for storytelling. Despite their mainstay status in late 20th century video and role-playing games, underground, monster-filled settings have been capturing our imaginations since long before Dungeons and Dragons and its ilk. Today on A Reception Collection, I’m exploring a game that marries recent gaming aesthetics and mechanics with some enduring ancient mythology. It’s a glorious example of layered reception, the idea that media based on ancient history and myth draws from antiquity, but also from more recent explorations of ancient visuals, characters, and ideas.

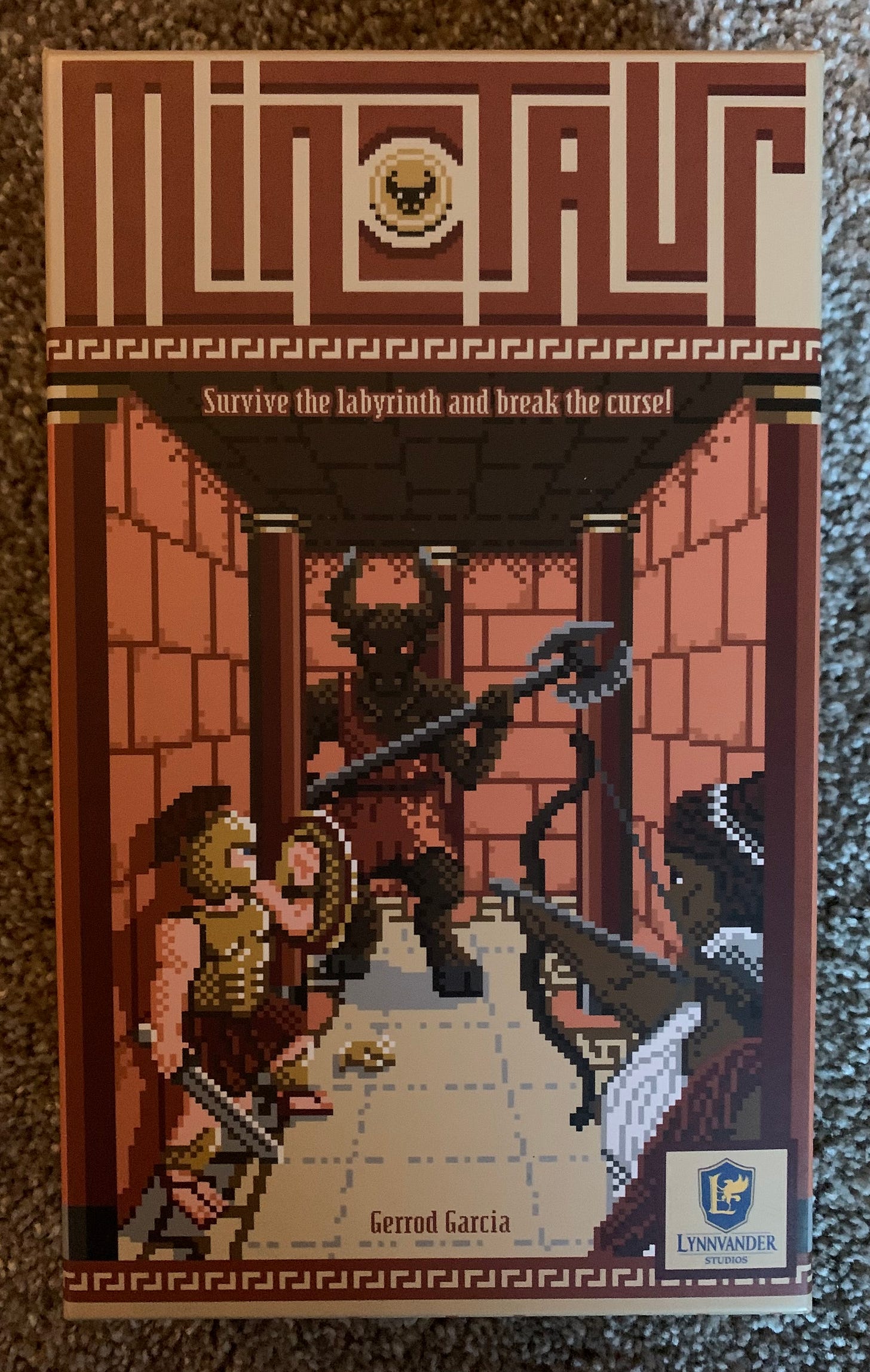

This is Minotaur, a 2023 co-operative tabletop game designed for 1-4 players. In co-operative gaming, players have to work together to achieve a common goal: in Minotaur’s case, they’re exploring an underground labyrinth, fighting off monsters. They have to fight a series of small monsters before working up to the “boss” of the labyrinth, the Minotaur himself.

Unlike the Minotaur in Greek mythology, who is very mortal this Minotaur cannot be killed. The labyrinth where he lives keeps him alive, regenerating him whenever he would otherwise die. Because of this regeneration, the players need to imprison the Minotaur in his labyrinth, to prevent him from going free and killing innocent people. They’ve journeyed into the labyrinth on a protective mission.

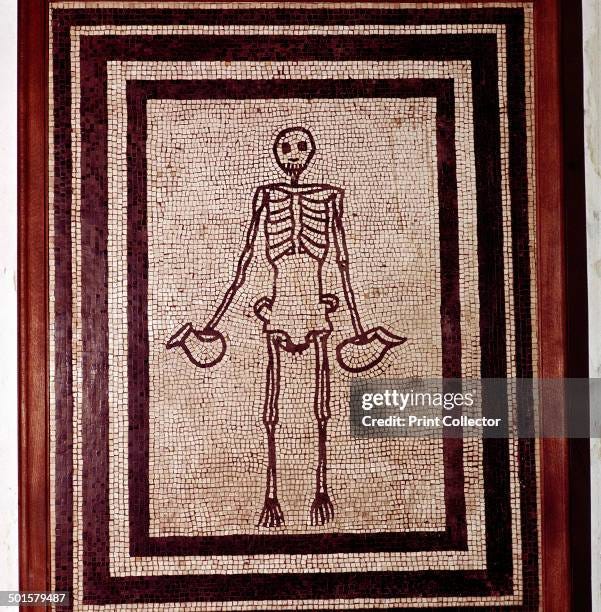

In addition to the titular monster, Minotaur features smaller foes in the form of animated, sword-wielding skeletons. These do not feature anywhere in ancient mythology: however, a similar band of skeletons stars in the climactic sequence of the 1963 sword-and-sandal film Jason and the Argonauts. Stop-motion animated by Ray Harryhausen, these skeletons are a landmark in filmmaking history, as well as one of the most memorable aspects of one of the most influential and enduringly popular films depicting a Greek myth.

Other media with a Greek mythological theme features fighting skeletons like these: they’re one of a few hallmarks of modern mythological pop culture that don’t actually originate in antiquity. (The Kraken, found in Clash of the Titans but nowhere in ancient Greek sources, is another well-known example.) I don’t have any complaints about this lack of accuracy to ancient myths: I read Minotaur’s skeletons as an homage to Jason and the Argonauts. Their presence here places Minotaur in conversation with older myth-based media and reminds its players of some classic films and visuals. Plus, the Greeks and Romans would have loved animated skeletons!

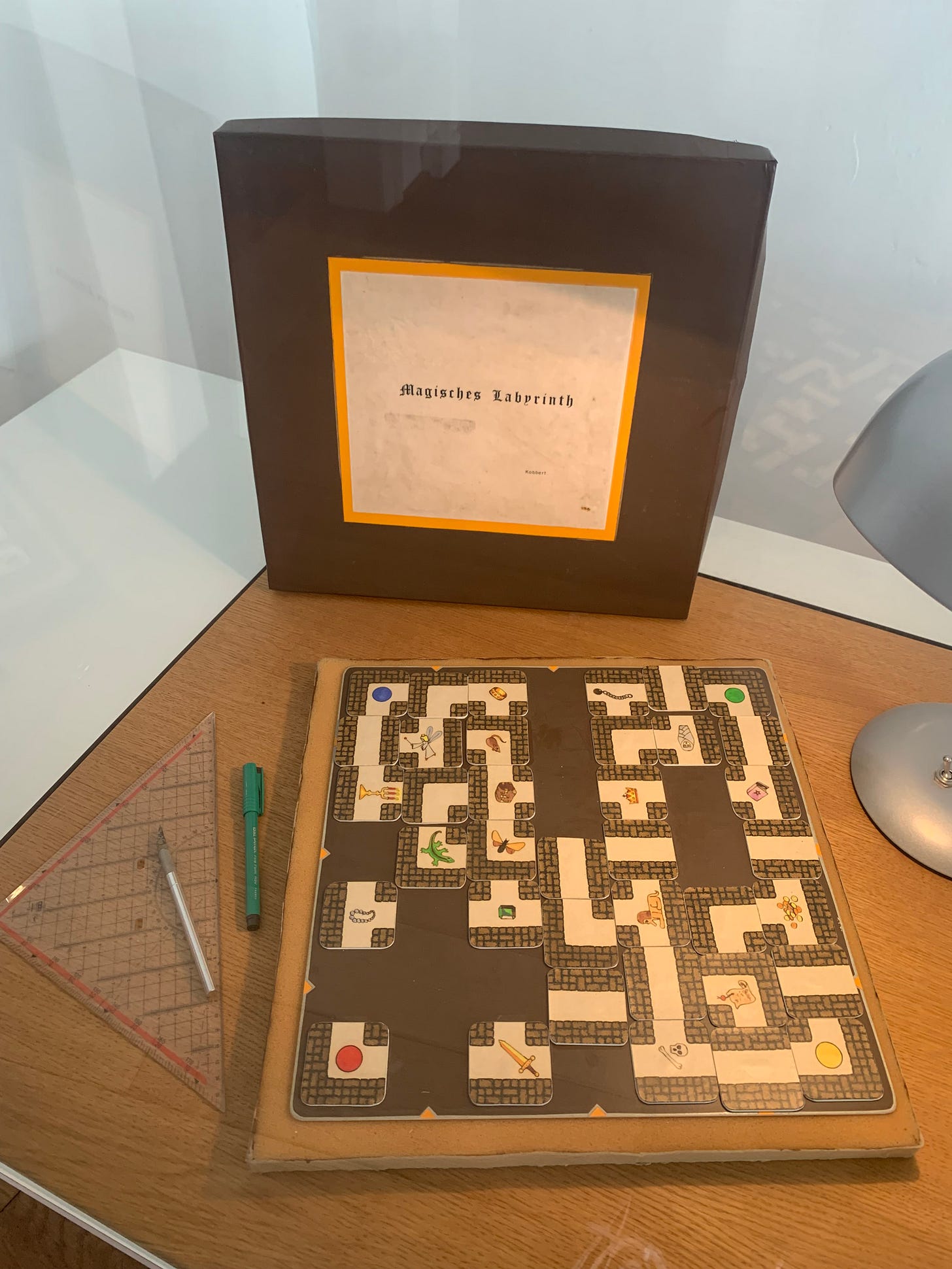

Beyond its choice of monsters, Minotaur engages in further reception of carefully chosen past media. Its core mechanic, a maze constructed of unpredictable shifting tiles that players must navigate at their own risk, has much in common with an older and simpler tabletop game, Labyrinth. First published by Ravensburger in 1986, Labyrinth features a board with channels through which tiles can slide, forming a constantly moving path where players wander in search of treasure.

Labyrinth is one of Ravensburger’s best-selling and most enduring products, and a classic in the realm of fantasy board games. When I visited the Ravensburger Museum in Germany last summer, they had an entire gallery dedicated just to Labyrinth! The mechanics for Minotaur are a little more elaborate, and Labyrinth is competitive rather than co-operative. That being said, the former game reads like a descendant of and perhaps an homage to the latter.

Minotaur features one more example of layered reception I’d like to discuss: the reception of ancient-themed video games. Its pixelated artwork deliberately evokes arcade and early console game visuals from the 1980s and 1990s. These early video games, as well as Labyrinth, were produced by a generation of creators who had grown up with the sword-and-sandal films of the early 1960s. They would have no doubt been familiar with Jason and the Argonauts and other midcentury sword-and-sandal movies. Minotaur’s artwork therefore engages with a few different eras of mythologically receptive media. It’s nostalgic for these old movies and games, but also introduces them to new generations.

In addition to looking back at video game history (while transposing it to an analogue medium!), Minotaur deploys some themes that are popular in recent video games. There’s one game in particular that has plenty of common ground with Minotaur: luckily for my research process, it’s a game I’ve played extensively.

The 2020 modern classic Hades features hoards of creatively designed monsters, all based on creatures from myth, with the exception of some Harryhausen-style fighting skeletons. Like the title character in Minotaur, these monsters can regenerate. To the chagrin of unlucky players, sometimes they regenerate in the midst of combat!

Both Hades and Minotaur take place in subterranean realms with stone walls, narrow dungeon pathways, and opponents at every corner. They also feature monsters who behave antagonistically toward players, who are positioned as outsiders in an underground realm. The monsters are obstacles to player achievements —in Hades the monsters have been explicitly ordered to act as obstacles—but players are not actively encouraged to think of themselves as antagonists or invaders. In Minotaur, even if they’re not encouraged to think of themselves that way, I can’t help but wonder how the inhabitants of the labyrinth perceive the player characters. Are they frightened? Stressed?Annoyed? If the players explained their goal of trapping the Minotaur to prevent him from killing their people, would he and his subterranean ilk understand? These are questions left unanswered by the game, which I would love to see explored in future tabletop creations. For now, Minotaur feels like a step in the right direction. An older game would probably have its players just kill the monster, and would have players enter the labyrinth to win glory, not to protect innocents.

Through this multitude of influences, Minotaur gives its players a subtly multi-temporal experience, mixing ideas and visuals from antiquity, several decades of the 20th century, and recent trends in the treatment of myth in popular media. It wraps these influences in a surprisingly pacifist bundle, since the players’ goal is not to kill the Minotaur. Minotaur and other games in its vein create a strong sense of layered reception, placing the tabletop world in conversation with past decades of media that engages with the ancient past, as well as with antiquity itself.

This game analysis is, once again, adapted from a section of my thesis. If you watched my lecture on games and mythology from back in January, some of the material might be familiar!

An Update on my Research: A Mythological Lecture

Happy late winter/early spring, my magnificent readers! I have an exciting thesis update for you. A few weeks ago, I gave a talk with the Centre for Hellenic Studies at SFU, which is my current home university. It was all about how modern board games depict Greek mythology: in my opinion, fascinating stuff!

As always when I make my thesis writings into blog posts, here are my sources:

Arthimalla, Jaswanth. “Rescripting of the Genre Through Greek Mythology in Hades.” Games and Culture Vol. 9 Issue 4 (2024), 535-545.

Johnston, Sarah Iles. “Narrating Myths: Story and Belief in Ancient Greece.” Arethusa Vol. 48, No. 2 (2015), 173-218.

Nisbet, Gideon. Ancient Greece in Film and Popular Culture. Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 2008.

Parlock, Joe. “Origins Hall of Famer Max J. Kobbert on Almost 40 Years of Labyrinth,” The Gamer, June 24th 2024, accessed December 2024. Link here.

Rollinger, Christian (ed.). Classical Antiquity in Video Games. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Solomon, Jon. The Ancient World in the Cinema. Revised and expanded edition. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2001.

Tiaynen-Qadir, Tatiana, and Qadir, Ali. “The Uncanny: Monsters, Blood, and other 3 A.M. Horrors.” In Tatiana Tiaynen-Qadir and Ali Qadir, Symbols and Myth-Making in Modernity: Deep Culture in Art and Action (Anthem Press, 2022), 53-75.

Willis, Ika. “Contemporary Mythography: In the Time of Ancient Gods, Warlords, and Kings.” In Vanda Zajko and Helena Hoyle, A Handbook to the Reception of Classical Mythology (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), 105-197.

A very fun analysis to read. Thank you so much for reading my paper!

Fascinating analysis. I love those old Harryhausen movies, especially Jason and the Argonauts (the skeletons are the best scene in the movie). :-)