As many of you already know, my upcoming thesis deals with board games. Specifically, it deals with how board games portray ancient Greece and Rome. I recently finished the first draft of a chapter about how games portray Greek mythology: it’s fascinating stuff, and I can’t stop thinking about it. Today on A Reception Collection, I’d like to discuss one of the games that features heavily in that chapter, and deals with Greek mythology in a very thought-provoking way.

Santorini is a strategy game that was first launched in 2016. Since then, it’s seen multiple expansions and add-ons. I’m focusing on the core game today, because it’s a fascinating encapsulation of how modern pop culture deals with Greek mythology.

As you can probably tell from the visuals I’ve shared so far, Santorini’s visuals are based on Greek architecture, specifically from the Cycladic islands. The game also incorporates some bright, cartoonish illustrations that wouldn’t be out of place in a children’s mythology book. The gameplay is fairly simple. Two players move worker figurines around the board, and build towers out of plastic blocks based on the position of their workers. The first player to climb one of their workers to the top of a block tower wins.

These basic rules of play make for a surprisingly tricky little strategy game. However, the fun of Santorini only starts there. The game features a deck of cards, each one representing an ancient Greek mythological character. This is where things really start to get interesting!

At the beginning of a round, players can draw one of these ‘god cards.’ Every card grants players a unique power for the entire duration of the game. Once per turn, players can use their special extra ability. The powers these cards bestow are, for the most part, cleverly themed to their respective gods: Hermes lets his player of choice move greater distances, Hephaestus grants the ability to build more, and Athena’s power strategically limits the options of one’s opponent.

The gods cards add a sense of strategic complexity to Santorini, and make the game exciting to play again and again. They also add an imaginative layer to the game’s in-universe narrative. In our universe, a round of Santorini consists simply of two people getting together and playing a board game. But in the universe of Santorini, a round consists of an epic struggle between two Greek gods. They’re battling for control of an Aegean island, getting their favourite mortals to do all the dirty work. The mortals engage in a duel of wits, assisted and supported by the gods. It’s worth mentioning that a round of Santorini is quite short: the game can wrap up in as little as ten minutes. This encourages players to duel each other for multiple rounds: at the beginning of every round, they have to draw new god cards. Thus, in the game’s universe, the gods don’t stay loyal to their mortals of choice, and don’t stick around for very long…

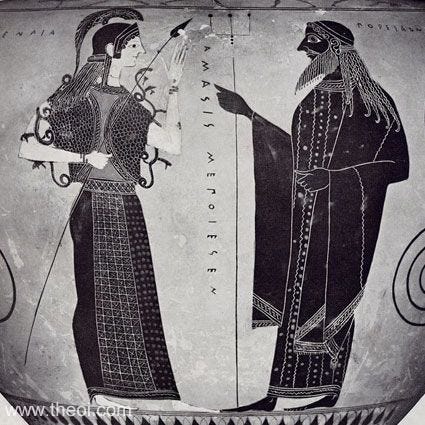

This idea of gods fighting for mastery of a place comes straight from Greek mythology. Perhaps the best-known example is the story of Athena and Poseidon’s contest for Athens. This myth involves the two Olympians fighting over who gets to be the patron god of a city they both fancy. They end up resolving their differences by each giving the city a gift, commanding its mortal population to judge the results and choose a winner. Because the mortals like her olive tree more than Poseidon’s impractically saltwater spring, Athena claims the city as her own. The mortals name it Athens in her honour, and it’s been her sacred city ever since!

Many ancient authors tell and retell this myth, including Ovid, Pausanias (who really sells it as the origin story for the city of Athens), Hyginus, and Apollodorus. I’m convinced that it at least partly influenced Santorini. The game’s cover art depicts Poseidon leaning excitedly over the island, moving part of a building into place. Interestingly, he’s joined not by Athena like in mythology, but by Aphrodite. Given Aphrodite’s notorious fondness for meddling in mortal affairs, I’m pleased with her inclusion here. Look no further than the Iliad for examples of Aphrodite stringing mortals along and messing with their lives. She also plays a supportive role to some of her favourite people: there are multiple scenes in the Iliad where Aphrodite protects mortals (usually Aeneas or Paris) from death on the battlefield.

Santorini isn’t the only piece of modern media that portrays this type of relationship between Greek gods and mortals. Friendly-but-fickle gods show up in plenty of video games. The Olympians in Hades help the game’s protagonist, Zagreus, by giving him temporary powers, but never by directly interfering in his quest. He can form stronger relationships with them by giving them offerings of nectar: a player in Hades can collect all sorts of rewards if they offer enough nectar to the gods.

Most of the Olympians are (frustratingly) antagonists in God of War: However, Athena serves as an ally for some games in the franchise. She aids the protagonist, Kratos, without completing his missions for him, in a manner that evokes her relationship with heroes in ancient texts. Her interactions with Kratos are especially reminiscent of how she treats Diomedes in the Iliad and Odysseus in all of Homer’s epics. In these video games, helpful gods allow players to gain power and progress through an unfolding narrative, while providing enough caveats and pitfalls to create a sense of uncertainty. You have their favour, but that favour might not last forever…

Interactive media, a category which includes video and board games, offers up great potential for these interactions between mortals (the players) and gods (in-game abstract forces, such as the cards in Santorini). The in-game forces represented by Greek gods here are beneficial to players, but also somewhat fickle. This fickleness and uncertainty gets amplified in games for multiple players. The gods in Santorini are nominally helpful, but there’s always a chance that they’ll be powerless against your opponent’s strategy. Since they’re not playing the game directly, what they can do to help is fairly limited. You’d think that, if they want control of this island so badly, they might interfere a little bit more, but no. That’s not the Olympian modus operandi!

I find it both fascinating and hilarious that Santorini involves a construction contest in ancient Greece, but the construction in question isn’t remotely ancient Greek. The buildings in the game, with their square white bases and blue domed roofs, are textbook examples of Cycladic architecture. The Cycladic islands, located in the Aegean Sea in Greece, have been around for millennia. However, this particular style of architecture has its roots in the 20th century. Buildings in the Cycladic style are famous around the world, in part thanks to tourism campaigns and appearances in popular media. They’re an iconic, instantly recognizable symbol of modern Greece. They also have nothing to do with antiquity!

This time-mashing juxtaposition of modern Cycladic buildings with ancient gods is emblematic of how we perceive Greece in western society. Ancient Greece holds such a sway and allure in western culture, especially ancient mythology. This is just informed speculation, but I have a feeling that most people (at least in North America) know more about Greek mythology than they do about ancient Greek history and modern Greece put together. That being said, some modern visuals are extremely prominent in popular ideas of Greece. If you do ask people what comes to mind when they think about modern Greece, they’re likely to mention those blue-and-white Cycladic buildings.

The prominence of these buildings in western perceptions of Greece is no accident. Mykonos and Santorini, which are both full of Cycladic architecture, are some of the country’s busiest tourist destinations. They’ve been that way since the 1960s and 1970s, when Greece started to seriously expand its tourist infrastructure. In fact, partly because of an explosion of social media exposure, Santorini has experienced ‘overtourism’ in recent years, to the detriment of people who live there. This popularity of Santorini the island undoubtedly contributed to the success of Santorini the board game. The game’s title carries connotations of relaxation and pleasure, no matter how noisy and congested an actual trip to Santorini might be these days. This name recognition, combined with the game’s cheerful visuals, give Santorini a sunshiny allure. I think it’s also a stroke of marketing genius that the game combines Cycladic architecture with ancient mythology. For a North American audience, these two things are often what first comes to mind when people think about Greece.

It doesn’t matter to game players that Cycladic buildings and Olympian gods are separated by a few millennia. Santorini revels in this architectural anachronism, and doesn’t bother trying to explain it. The game’s cartoonish visual feel helps with this: it makes the blend of time periods feel deliberate, and in good fun. Personally, I’ll let the cross-temporal mashup in Santorini slide because its actual gameplay has such close ties to how the ancient Greeks perceived their gods. In a game with a more serious tone, or with less thought put into the treatment of mythology, the anachronism wouldn’t work the way it does here. The world of Santorini mixes modern aesthetics and ideas about how Greece looks with a mythologically attested vision of the relationship between mortals and gods. It’s a joyous little strategy game, and I’m delighted to include it in my thesis work on how tabletop games portray Greek and Roman antiquity.