Does anyone else remember the Getty Challenge?

In my opinion, it’s one of very few good things to emerge from Covid. The Getty Challenge officially began on March 25th, 2020, when lockdowns were a new idea, vaccines hadn’t been developed, and the world was full of uncertainty and fear. As the name suggests, it was a social media project, initially launched on the Getty Museum’s Twitter. The challenge rules were simple: using ordinary objects and inhabitants of your living space, recreate a famous piece of art. Then, share the original art and your recreation side by side online.

The original March 25th tweet suggested that participants use at least 3 household objects to make their recreations. However, as you’ll soon see, challenge entries quickly got more and more elaborate. The museum’s staff posted a few sample pictures, like the found-object version of JMW Turner’s “Modern Rome” above, but the general social-media-using public got the idea right away. Soon, the Internet was teeming with these household art copies.

The Getty Challenge involves art from around the world and all through time. Since this is A Reception Collection, let’s take a look at some challenge entries that engage with ancient Greece and Rome. There are lots of entries that replicate ancient art, while others imitate later works that feature Greco-Roman themes. I have some general thoughts on historical reception in times of crisis and in digital space, but I’ve saved them for the end of this post. First, let’s enjoy some art recreations.

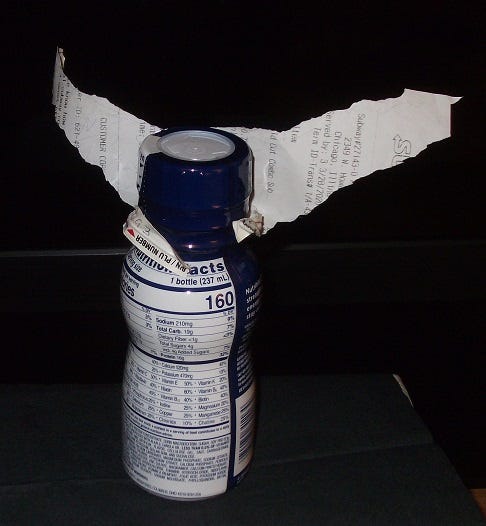

This take on Nike of Samothrace is an early entry to the challenge, posted to Twitter on March 29th, 2020. The original Hellenistic-era statue lives in the Louvre and is made out of marble, while the pandemic-era copy consists of an empty plastic bottle and a fast food receipt! I admire the simplicity of this one, as well as the subtle attention to detail. The dramatic lighting is a fun touch, and the curves of the bottle nicely mirror the contour of Nike’s body. There’s a lightheartedness here: I appreciate it now, and appreciated it even more in 2020. This challenge fostered a sense of community and collectivity in a time period marked by extreme isolation. At least, it fostered that community for art history nerds like myself!

“Woman Picking Flowers” is a 1st century CE fresco from a house in Pompeii. Telma Har’s recreation is a photo from 2021. Her artistic pose and prop choices remind me of later engagement with ancient imagery, especially post-ancient takes on Greek and Roman femininity. Har could pass for a Pre-Raphaelite painter’s model, or part of a Victorian tableau vivant. The plastic bush adds just a little touch of kitsch.

Speaking of Pre-Raphealites, here’s Circe Invidiosa by John William Waterhouse, recreated by a high school student from New Jersey. One of her teachers made the Getty Challenge into an assignment in the spring of 2020, and the school shared the project online. I have mixed feelings about this. Part of the joy of the Getty Challenge is its spontaneity, with people choosing to participate for fun: making students do it for class loses a bit of the magic. On the other hand, this is an offbeat and clever way to get teenagers to approach art history. Judging by the pictures from this school, the assignment encouraged students to think about image composition and lighting, get creative with props, and look at art pieces in an unusual way. Some of the students took their recreations in a gleefully silly direction, like this towel-based Roman bust:

The recreation model’s face is doing some heavy lifting here. I love how they look a bit bored or vacant, like someone stuck in a dull meeting. I wasn’t able to find the title of this particular sculpture, but my guess, judging from the hair, is that it’s a wealthy woman from the Flavian dynasty, who ruled the Roman empire in the late 1st century CE. They were fond of huge high-fronted curly hairstyles, which look rather cartoonish by modern aesthetic standards. If you know who this ancient woman is, please leave her name in the comments!

Going further back in time, Facebook user Irena Ochódzka imitated a Cycladic marble sculpture, which dates back to the 3rd century BCE. The ancient sculpture features a lyre, but her rendition uses a vacuum cleaner!

This entry got quite a bit of recognition: I remember seeing it all over my (admittedly classics-inflected) corner of social media in the spring of 2020. In fact, the Getty’s antiquities curator, David Saunders, hand-picked it as one of his favourite challenge entries in a December 2020 missive on the museum’s website. While singing the praises of the Cycladic vacuum, he drew attention to the contrast between the lyre and the mundane cleaning machine. Saunders remarks that “The ancient harpist used his instrument to sing of heroism and mythic valor. This new version seems to bestow a similar glory upon the daily tasks that continue during lockdown.” He does not bring up gender politics directly, but I can’t help but read into them here. Household labour is heavily associated with women, both in antiquity and (sometimes unfairly) today. Ochódzka’s vacuum could be giving the performers of daily domestic work their proverbial flowers by likening them to a Cycladic bard. Alternatively, she could be knocking mythical stories down a peg by bringing them to the world of the mundane.

This emphasis on the everyday is one of the many charms of the Getty Challenge. The entries here pick at the concept of ‘high art,’ and the notion that art is somehow separate from daily life. They’re not insulting famous paintings and sculptures by taking them out of their museum and gallery settings, but rather honouring them by connecting them to the everyday. They’re also adding to the process of Greco-Roman reception, in art pieces from or inspired by antiquity. Modern works engaging with the ancient world almost always incorporate visuals and ideas from later media, since western society has such a long-standing fascination with Greece and Rome. Direct copies of these works, including Getty Challenge photos, draw attention to this layered reception, while also adding a new layer of interpretation by using modern bodies and props.

Not to brag (okay, maybe a little to brag), but that aforementioned article from December 2020 includes my own contribution to the Getty Challenge. To the surprise of nobody who knows me, I recreated some artwork from ancient Greece. Achilles sulking in his tent spoke to me back then. In May 2020, I was spending a lot of time holed up in my bedroom, upset that I couldn’t do things like go to the gym, hang out with friends, or travel. I was especially miserable about a field school trip to Greece, which had fallen through for obvious pandemic-related reasons. I found Achilles’ melodramatic antics funny in a way that distracted from the frustrations of Covid, but I also related to him quite a bit!

The image of grumpy Achilles bundled in blankets is a common theme in ancient Greek artwork, so I had plenty of images to choose from. I settled on a vase painting, partly because I love them, partly because their minimalist colour scheme was interesting to recreate with objects around my family home. My own body is front and centre in my image, but the scene also incorporates a chair, a bedsheet, and one of my brother’s old hockey sticks. The backdrop is made out of a cape from an old Halloween costume, which I set up using tape and safety pins.

David Saunders said he was impressed by “the careful attention paid to the drapery’s rhythmic folds and the posture of the feet” in my version of grumpy Achilles (!!!!). He also delved into some ideas that are pretty emblematic of the early 2020s: “…with fabric masking his face, Achilles’ self-isolation mirrors our current experience. How much do we lose by cutting ourselves off from those who need us?” His analysis brings a legendary hero into the everyday, or at least the everyday of a very specific, difficult time period.

It feels discombobulating to talk about the early 2020s as a ‘time period.’ In my mind, they just happened: on the other hand, my life now is extremely different than it was in 2020 and 2021. Looking back to the worst years of Covid makes me think about the pace at which current events become history and ongoing life becomes memory. How soon should we start treating the recent past like history? When do we start preserving and cataloguing it?

Maybe my archivist biases are showing here, but, as I was collecting images for this post, I was struck by how complicated it was to gather a good amount of sources for Getty Challenge pictures. Online content is more ephemeral than we’d like to think. My own entry demonstrates this well: I participated in the challenge by posting to Twitter, a site I no longer use. Any links back to my account are dead ends. I copied my own Achilles photo from the Getty Museum’s website: I obviously have the original if they hadn’t documented it, but what if someone who didn’t spent May 2020 dressing up like a grumpy Achaean blanket warrior wanted to see the image? There were some Getty Challenge photos I ended up cutting from this post, because I couldn’t properly credit the people who assembled them. In the name of source integrity, I don’t love the idea of sharing those pictures. It probably shouldn’t bother me: images get shared online without credit millions of times every day. When you share a meme with your friends, do you ever stop and think about who made it? There are similarities between the Getty Challenge and memes: they’re online pictures, meant to be spread far and wide, for entertainment purposes. However, there are so many personal touches in the Getty Challenge, and so much creativity that I want to give credit where it’s due. Again, maybe I’m overthinking this.

Thinking back to living through the Getty Challenge, I largely remember it as a mental break. It was a way to connect with fellow art lovers and history nerds, but, most importantly, it was funny. Looking at silly, creative, irreverent pictures like the ones I’ve shared here was a means of carrying on in a time of crisis. I found myself thinking about this a lot as I wrote this post: while I was assembling challenge photos, the Getty Museum’s hometown of LA was devastated by wildfires. It seemed like a horrible coincidence. Imagine my relief when I checked the news and learned that their collection survived the fires unharmed!

When I first started writing this post, I thought of the Getty Challenge as a figment of the recent past, something that gradually died down as vaccines rolled out and the world emerged from the early Covid period. To my delight, my research revealed that it lives on. There’s a small but dedicated core of Reddit users who are making Getty Challenge-style art recreations to this day. Kudos to them for carrying on with this unique form of historical reception!

A lot of my adult life has been "but [time period] was just yesterday and also feels like one million years ago," 2020 more than most. What's been weirder for me is how many people talk about it like the distant past, and how jarring it is when someone brings up an aspect I did forget. Like this challenge, for instance. But what I do remember in 2020 was wondering how the art that was made during quarantine would be looked back on - I was thinking primarily of all the shows that did free specials and zoom reunions (Parks & Rec, the Dr Who spinoff the Sarah Jane Adventures, the LOTR cast, that Princess Bride challenge...), and like, how do you explain to someone who wasn't there why all these people filmed their parts separately on phones or webcams, out of their own houses or backyards? And sometimes the art just disappears. You don't think of preserving it often enough while it's happening.

I do love the Getty challenge, and especially that Grumpy Blanket Achilles!