Reception in Poetry: The Sphinx, by Oscar Wilde

Inviolate and immobile she does not rise she does not stir...

Happy Pride Month, my fabulous readers!

There are countless intersections between queer history and ancient Mediterranean reception. Plenty of queer artists have drawn inspiration from antiquity over the centuries, including some particularly beloved and well-remembered icons. It’s impossible to talk about queer literary history without bringing up Oscar Wilde. He was one of the most influential English-language playwrights of the late 19th century, a famous wit, and a pioneer of gay dandyism; he was also a prolific poet. Since this is Reception in Poetry, you can probably see where I’m going with this…

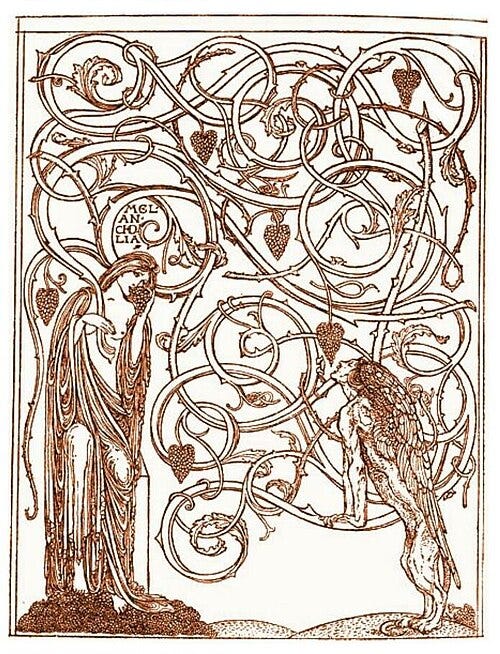

The Sphinx is a long poem, which Wilde wrote over the course of several years and eventually published in 1894. It’s a hallmark of the Decadence artistic movement of the late 19th century. Decadence prioritized excess, aestheticism, and lavishness in all their forms. The last Reception in Poetry post I wrote explored a poem that reacted against this type of artistic excess, so, in a way, we’re travelling back in time with this entry!

In this poem’s story, an ancient Sphinx materializes in the bedroom of a sleepless young student, who serves as our narrator. Wilde began this poem while he was a student himself, so this narrator is likely an author stand-in. The Sphinx slowly drives him to madness, until he finishes the poem begging for death. However, much of the madness stems from the narrator’s own mind, not from the Sphinx’s machinations. He spends much of the poem speculating about her life in the ancient world, her encounters with mythological and historical figures, and the wild, witchy extravagances of her past. Our narrator is particularly fixated on the Sphinx’s love life, probing her with questions about the gods and heroes she slept with, imagining their bodies and their dalliances. These ancient lovers are simultaneously dangerous to him (at one point, he grabs a crucifix in an attempt to banish the vision he and the Sphinx have conjured) and highly alluring. Since the Sphinx and her lovers are immortal, there’s a chance our narrator could join them, give in to his passion, and discover a new aspect of his sexuality.

If you’re a mythology nerd (technical term) like me, The Sphinx is a gold mine of references. Reading it is like reading a catalogue of our collective fascination with ancient Egypt across time. Since Egypt and Greece have several millennia of cultural cross-pollination to their names and Egypt was part of the Roman empire for centuries, reception of these three ancient cultures tend to bleed into each other. The Sphinx is no exception: the poem names plenty of creatures from the Greco-Roman mythos, including Gryphons and the Chimera, transposing them to the banks of the Nile.

Wilde’s focus is, however, mostly on Egyptian mythology. Thoth shows up, Isis shows up, Amon shows up in a big way as one of the Sphinx’s lovers. We readers encounter these ancient deities at the same time as later mythological/religious figures, from the virgin Mary (“sing to me of the Jewish maid who wandered with the Holy Child”) to the Minotaur (“sing to me of the Labyrinth in which the twi-formed bull was stalled”). The late 19th century saw a proliferation of archaeological expeditions, spurred by European colonial initiatives in Egypt, and a collective cultural fascination with Mediterranean antiquities. The Sphinx is very much in conversation with this fascination, treating Egypt as a place that’s both geographically distant and far away in time. There’s an aim for timelessness here, but this exoticized image of Egypt is firmly rooted in 1894.

My personal favourite references in The Sphinx are the ones Wilde pulls from recorded history. He imagines the Sphinx witnessing some famous Roman visitors to Egypt. Many of them been elevated to a near-mythical status in western culture, so they fit right in among the ancient gods and magical creatures. Antony and Cleopatra make a brief appearance, while Antinous, the Roman emperor Hadrian’s lover who famously drowned in the Nile river, gets several lines of poetry in his name. Our narrator imagines the Sphinx on the banks of the river, hearing Antinous laughing from the emperor’s barge and unable to take her eyes away.

Antinous here is a beauty with an “ivory body” and a “pomegranate mouth;” it’s tough to read his description as anything but homoerotic. Wilde taps into a storied tradition of using the ancient Mediterranean to explore contemporary sexuality, especially same-sex attraction. Antinous’ appearance is perhaps the most overt passage in The Sphinx, in terms of a gay male gaze. However, the whole poem revels in a specifically queer vision of antiquity, with its lavish depictions of beautiful bodies in a dreamlike place.

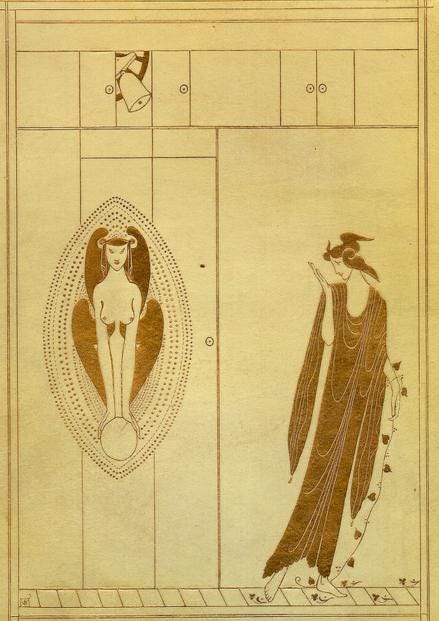

Normally, I end my Reception in Poetry posts with the text of the poem in question. However, The Sphinx is very long, so I’m better off sharing a link. Here’s a plain text version and an illustrated Victorian copy of the poem. Take your pick, and happy reading!